If there’s a pragmatic approach to sustainability, there’s no better person to consult than my mother, a full-blooded Ilocano. Born with bucolic roots in the province of Nueva Vizcaya, she carries the Ilocano reputation of being kuripot very well.

“Ag kakasar manen ta il-ilawen,” (The lights are getting married.) she would always gawk at me in her usual imposing voice when I forgot to turn off the lights in our balcony and sala. Back then, I didn’t get the wisdom of that idiom, which she probably just made up.

My mother loves natural light. Even when green architecture was still considered revolutionary in the 80s and 90s, our house was designed with high exterior glazing and windows to allow daylight and good outside airflow.

Quite the contrary, I enjoyed dimly lit and somber room more when I was younger. Sometimes, this would wrestle with my mother’s commitment to her energy conversation practices. “Nakasisipngetan. Kasla ka manggagamud.” (It’s very dark. You’re like a witch.) This would always leave me confused. I faced the trauma of exercising my own judgment when or when not to turn on the lights at an early age.

For years, our parents and the parents before them have tried to educate us on the importance of the environment, well sometimes inadvertently. Across cultures and traditions, there’s a common message – nature is far greater significant than of any of us.

Freniel Austria

The concept of manggagamud is widespread in the rural North. They are thought to conjure and inflict pain to their victims using satanic or diabolical means. Ilocanos believe that the spirits of nature have the gift to counter these evil deeds. This is heavily influenced by folk beliefs and rites that nature has spiritual essence.

Growing up in a cultural divide, where modern ideologies dismiss or even frown upon these ethnological narratives and beliefs, my mother continued to embrace and teach me folk culture and customs. She is a very rational person but it has been culturally ingrained in her to hold on superstitions at times.

When I was a kid, she taught me to say “bari bari” when I go to remote, unvisited vegetation or tree-laden areas. The reason was very primitive then, she told me that engkantos protecting the natural world would get angry if I invade their supernatural abode.

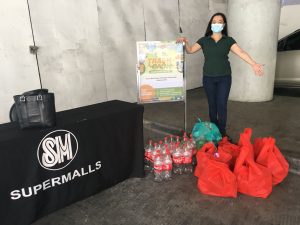

Image credit: Pola Sagabaen

As I turned teenager, I disregarded “bari bari” as only a gimmick to scare children not to wander off. I didn’t think of the deep reverence that my elders have on nature. I failed to notice it as part of a general environmental consciousness.

Another Ilocano culture is forbidding unnecessary destruction of nature. “Makasarsarak” in vernacular spirituality has taught generations to avoid disturbing nature and leaving anything. While the “Leave No Trace” seems like a newfound element of outdoor ethics, minimizing negative environmental and ecological impact has been a fundamental value of Ilocanos.

My mother also believes that planting seeds contribute to the prosperity of the household or community. While I am not credulous enough to believe in this claim, it has been evident and even backed by science that nature has a salutary effect to our health.

Image credit: Pola Sagabaen

For years, our parents and the parents before them have tried to educate us on the importance of the environment, well sometimes inadvertently. Across cultures and traditions, there’s a common message – nature is far greater significant than of any of us.

But as these traditional beliefs on the role of nature and how the world works is slowly dying, we are starting to achieve a momentous success as government and corporate policies are recognizing the need for environmental sustainability and justice.

For some, environmental sustainability and development is a new idea. But I believe that our Filipino values to be close with nature and our innate tendency to feel responsible for it have always been there. Change doesn’t always mean we forego the old ways. “Bari bari” is not fear of the unknown, but a mantra to set the groundworks of my individual efforts to achieve sustainable living. No matter how small the change from my stories and actions would make, I sustain!

Reading your article helped me a lot and I agree with you. But I still have some doubts, can you clarify for me? I’ll keep an eye out for your answers.